Through participation in a prestigious international challenge, three Pace students envisioned a future to improve the infrastructure surrounding pedestrian safety at New York City intersections.

Using African Fashion to Correct AI Bias

Artificial intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are constantly in the headlines, from advancements in access to ethical concerns about the impact on human labor and specific groups. For computer science experts like Christelle Scharff, PhD, the focus lies less on what AI can and will do and more on its current limitations, especially when it comes to incomplete datasets that illustrate bias in these AI systems.

Scharff has been at Pace for 22 years as a professor of computer science, and she’s currently associate dean of the Seidenberg School of Computer Science and Information Systems. When she began exploring AI as a PhD student, she described her work as mostly “theoretical”, working on theorem proving problems. She was fascinated with studying how a computer can understand mathematical and logical concepts like deduction rules, equality, commutativity, and associativity. As AI technology developed, so did her interest in machine and deep learning and also in mitigating potential biases in AI. Scharff’s research has been focusing on Africa since 2009 when she received a grant to work on entrepreneurship and mobile app development in Senegal. Since that time, more opportunities to study AI in Africa arose and now Scharff and her students are continuing to explore how to ensure AI keeps up with growing global inclusivity.

As AI technology developed, so did her interest in machine and deep learning and also in mitigating potential biases in AI.

Two of her most recent projects with PhD students, Kaleemunsia and Krishna Bathula, center on African fashion. The first sought to expand the scope of a popular fashion dataset called Fashion MNIST. Datasets are the pillars of the AI movement, and safeguards are required to create and use datasets.

While Fashion MNIST is able to identify certain garments, fashion items that fall outside its very limited descriptions (which mostly fall under Western terminology and trends) are easily misclassified. “If you ask this dataset to recognize a sari, it’ll probably tell you it’s a dress,” Scharff says as an example. She explains that like with the sari, this dataset doesn’t know how to identify specific African fashion items. “Because I worked in Africa as a Fulbright Scholar, I focused this project on African fashion and involved graduate students from Senegal.” The plan was to create a dataset to address African fashion and recognize two popular Sengalese garments: boubou and taille mame. To put the importance of incorporating a wider, more global language into these AI models, Scharff explains, “If you were to go to the tailor and say, ‘I want a dress’ the tailor wouldn’t know where to start.”

"The other step in any project related to AI is that you need to ask the subject matter experts."

—Scharff

The other African fashion project Scharff and her team worked on is likely more tangible to those outside of the AI community. They worked to recreate a popular pattern in Africa called wax—a colorful, geometrical pattern that is often shined with wax.

The team collected a dataset of around 5000 free wax patterns and created new, satisfying patterns that are AI-generated. From there, the team printed select patterns and partnered with local artisans in Senegal to create fashion items including bags. The dataset was built to generate a variety of patterns. To get a proper sample, one needs upwards of 10,000 different images, Scharff estimates. If a dataset had mostly blue patterns, the generative patterns would stick mostly to blue, or if there weren’t enough floral images, they would need to add those images to the dataset to get them. The very nature of exclusion changed what the AI could produce, demonstrating the need to expand these datasets to reflect the world as it is, not just what has been inputted thus far.

Her students are hard at work, building out that dataset and corresponding models to generate interesting wax patterns.

"My biggest concern is diversity biases. But I think right now the discussion is much more open, at least everybody is aware of the issue. So, then it's a question of having the policies, tools, processes, practices to make it completely happen."

—Scharff

And for those worried about the AI takeover of jobs? “The other step in any project related to AI is that you need to ask the subject matter experts,” Scharff says. She explains that once these patterns were created, they need to be reviewed by fashion experts to understand what was working and what wasn’t. A computer can create a pattern, but it can’t (as of yet) also categorize it as what is fashionable for everyday wear, artistic, or what kind of aesthetic category it belongs to.

Scharff is excited for where AI is going, and how ubiquitous it’s becoming. Her greatest concerns are exactly what her work is doing, balancing datasets to be representative and diverse. “My biggest concern is diversity biases. But I think right now the discussion is much more open, at least everybody is aware of the issue. So, then it's a question of having the policies, tools, processes, practices to make it completely happen.”

More from Pace Magazine

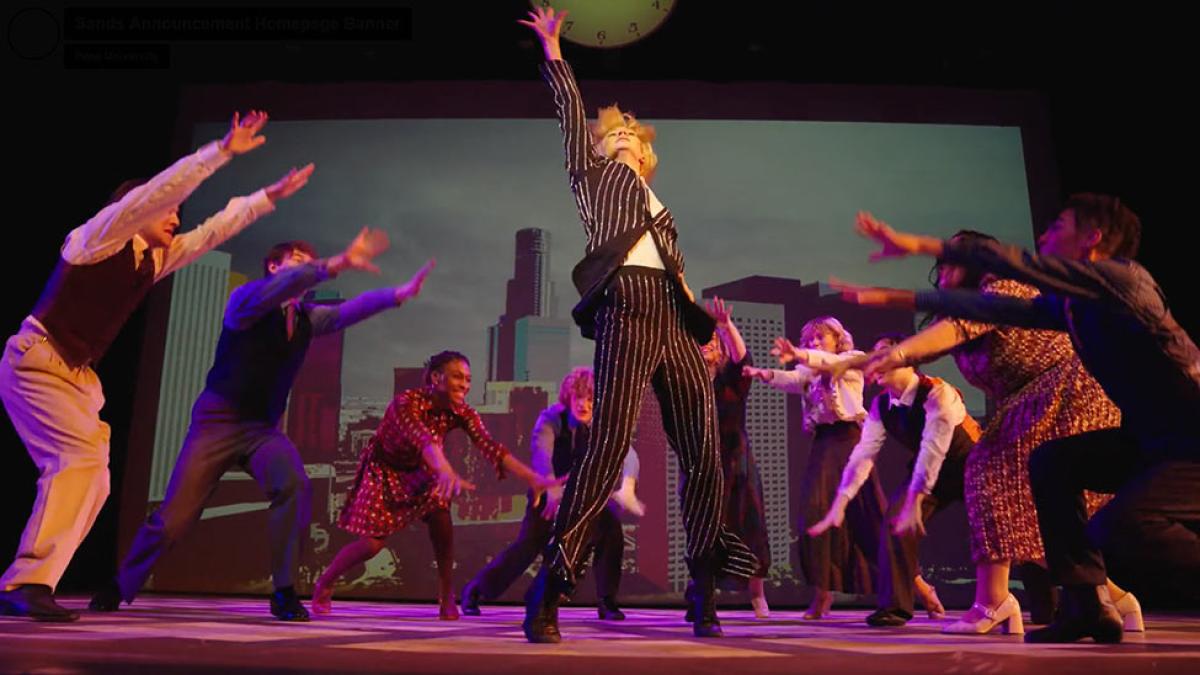

The launch of the new Sands College of Performing Arts, another year in the #1 slot for environmental law, a ton of awards and research, plus so much more. Here are your Summer 2023 top 10 Things to Inspire.

For 42 years, Ellen Sowchek has been sharing her infectious enthusiasm for Pace University history. Take a look at five of her favorite finds from the University archives.