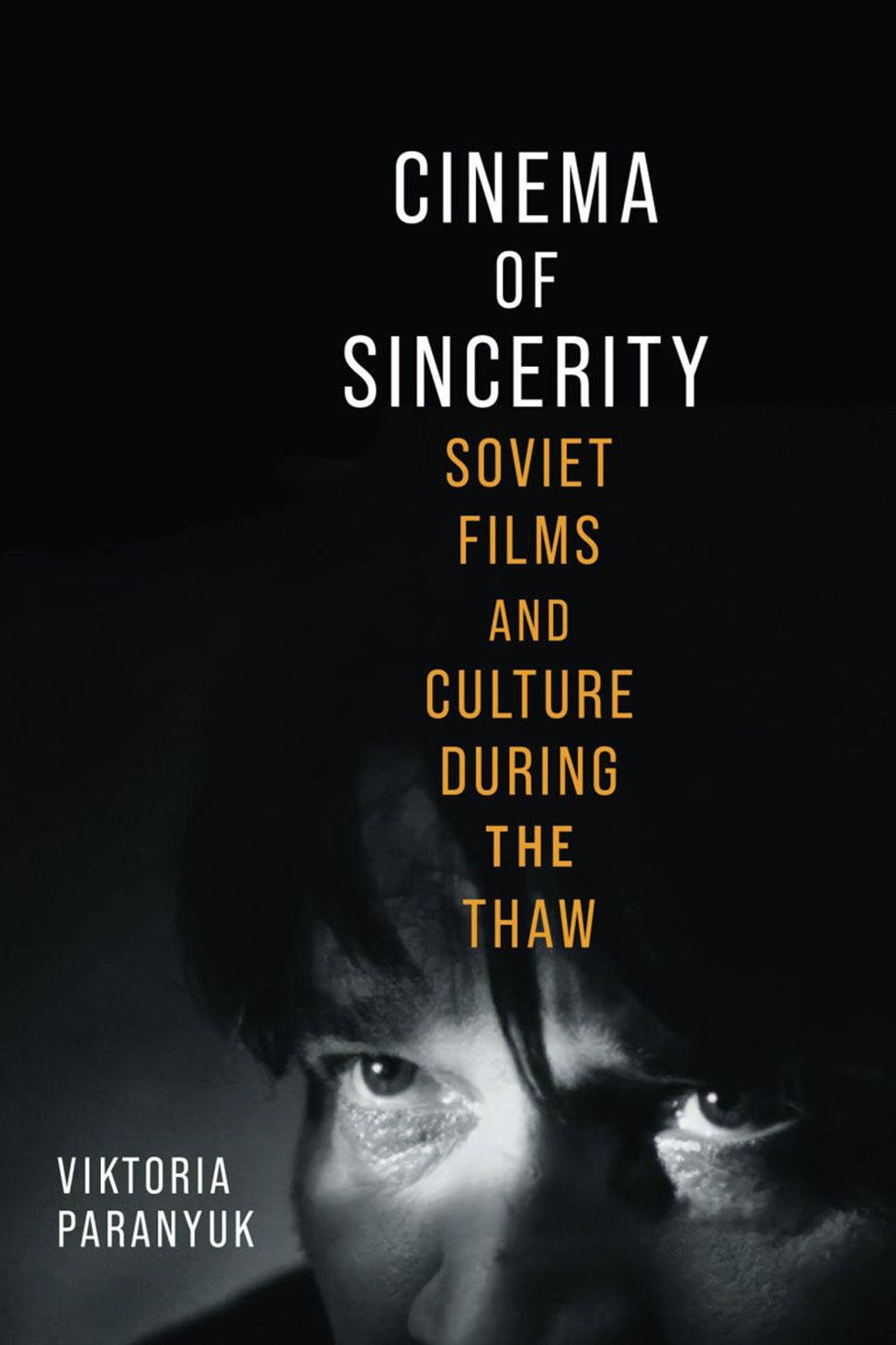

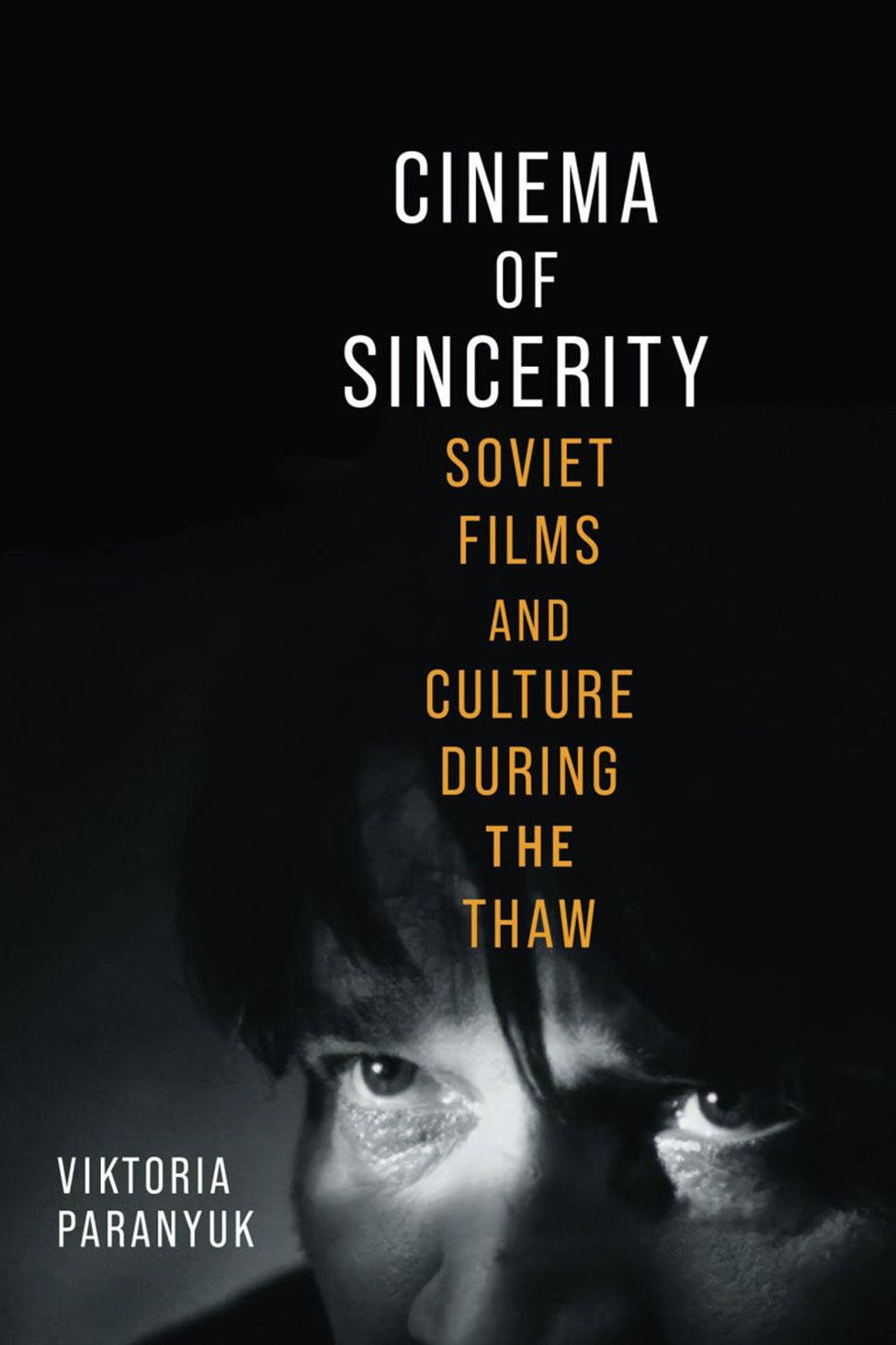

Cinema of Sincerity: Soviet Films and Culture During the Thaw

Viktoria Paranyuk, PhD

Lecturer, Film and Screen Studies

What is the central theme of your book?

Cinema of Sincerity: Soviet Films and Culture During the Thaw is about the efflorescence of Soviet cinema during what came to be known as the Thaw, a period of relative political softening after the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and before the Soviet tanks rolled into Prague in August 1968. Unlike the inflated confections of the Stalin era, the cinema of sincerity turned inward, insisting on ordinary characters and their interiorities, and created a sense of spontaneity via particular staging methods and cinematic techniques, among them, the close-up, the handheld camera, and interior monologue. My book shows that Soviet cinema of the 1950s-60s was the multigenerational effort that developed and thrived in centers outside of Moscow and which, taken as a whole, came up with renewed visual language and created works that opened up space for a collective self-examination.

What inspired you to write this book?

The initial inspiration came from the films themselves: their innovative style and thematic boldness. Additionally, I wanted to reweigh the standard historical accounts of Soviet cinema by diminishing the role of the centralized Russian state and instead highlight diverse individuals and filmmaking practices, especially in places away from the imperial center. Without minimizing the highly repressive regime in which these artists worked, I also wanted to shift the focus to less official forms of interaction, such as friendships and collaborations; teachers who bucked the prescribed curriculum by introducing movies or texts they were not supposed to; translators who shared their knowledge of different film cultures; and other informal exchanges of knowledge, ideas, and aesthetic forms. I was interested in these small spaces of resistance.

Why is this book important in your field? What does it contribute to the current body of knowledge on this topic?

Cinema of Sincerity is an important contribution to the fields of film and media studies and Slavic studies, bringing work of lesser-known filmmakers, among them Marlen Khutsiev, Tengiz Abuladze, and Arūnas Žebriūnas, and of critics who shaped vibrant discourse, among them Maya Turovskaya, to the center of postwar cinematic modernity. My book is the first to take the term “sincerity” seriously in film studies. It is true that sincerity became a cultural imperative, a mantra in post-Stalin society, but I argue that in the Soviet context it can be understood not merely as a slogan but as an aesthetic strategy as well as a reworking of a trend in global cinema that sought to bridge the gap between reality and the filmed image. I put Soviet sincerity in conversation with Italian Neorealism, for example. Additionally, Cinema of Sincerity challenges several commonplaces in film historiography, demonstrating that Soviet filmmakers and critics participated in a multidirectional flow of ideas between East and West and beyond; that Soviet cinema had a significant impact on other cinemas; and that it was not always controlled in a top-down manner as is often assumed.

Tell me about a particularly special moment in writing this book.

Interviewing cultural figures who had witnessed and taken part in the renewal of film culture in the 1950s and 60s was probably the most memorable. For instance, I spent several hours on a summer afternoon in Maya Turovskaya’s apartment as she recalled the heady and complex times of the Soviet Thaw.

What is the one thing you hope readers take away from your book?

I would like readers to know that Soviet cinema does not equal Russian cinema. It comprised many cinematic traditions, each with its own language, thematic preoccupations, and aesthetics. And I hope some readers might be compelled to seek out one or two of the films I discuss.

Fun facts:

When did you join Dyson College?

Fall of 2019.

What motivates you as a teacher?

I love seeing students get excited about an idea or an observation during class. As a teacher, there is no better reward for me than a motivated, engaged young person.

What do you do in your spare time; to relax/unwind?

Hang out with loved ones, read, or watch something fun.

What are you reading right now?

At the moment I’m in the midst of Kate Atkinson’s absolutely captivating novel Life after Life, Lyndsey Stonebridge’s We Are Free to Change the World: Hannah Arendt’s Lessons in Love and Disobedience, and Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg’s Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image. I recommend all three.