Mamdani Still Favored In NYC Mayor's Race

Dyson Political Science Professor Laura Tamman tells Newsday that Mayor Adams’ exit from the mayoral race is “a major shake-up” that redefines the contest. Professor Tamman notes that the race’s new dynamics underscore the importance of coalition-building and voter mobilization.

A Shameful Indictment

Professor Gershman pens an op-ed in The New York Law Journal, titled “A Shameful Indictment,” which denounces the lack of prosecutorial accountability and calls for urgent reforms to protect fairness and integrity in the justice system.

Hidden Crisis Behind Korea’s Suicide Numbers

Dyson Communication and Media Studies Professor Seong Jae Min writes a piece in The Korea Times exploring South Korea’s deepening suicide crisis. He argues that behind the troubling statistics lies a complex interplay of economic stress, societal pressure, and the influence of cultural taboos around mental health.

6 Supplements That Could Lower High Blood Pressure

CHP Director of the Nutrition and Dietetics Teaching Kitchen Mary Opfer speaks to News Break about supplements that may support healthy blood pressure, highlighting the role of omega-3 fatty acids in vascular health.

3 Unique Programs at Westchester Universities Prep Students for the Future

Westchester Magazine features Pace’s B.S. in Game Development program, highlighting how students transform their passion for gaming into successful career paths. With a curriculum spanning computer graphics, AI, and storytelling, the program positions students to thrive in one of the fastest-growing creative industries.

Pace University Partners with Westchester County to Address Hispanic Community Needs

- Read more about Pace University Partners with Westchester County to Address Hispanic Community Needs

News 12 Westchester reports on a groundbreaking Hispanic Community Needs Study conducted by Pace University – under the direction of Interim Associate Provost Rebecca Tekula and her MPA team – in collaboration with Westchester County Government. The study—first of its kind in over two decades—reveals key challenges facing Hispanic residents, from housing and healthcare access to workforce pathways divided by language, and recommends targeted policy responses like expanding affordable housing and bilingual health services— and Talk of the Sound has the story.

Preparing the Next Generation of Healthcare Workers

Pace University has been awarded more than $3 million from the New York State Department of Health’s Healthcare Education and Life-skills Program (HELP) to establish the College of Health Professions Pathways to Practice Initiative (CPPI.

Finding Community and Opportunity at Lubin

From Red Bull events to leading AMA, Anna Li is turning campus involvement into career-ready experience and discovering her passion for marketing along the way.

Anna Li

Class of 2027

Pronouns: She/Her

Currently Studying: BBA in Advertising and Integrated Marketing with a minor in Finance

Member (Clubs): Chief Financial Officer of the American Marketing Association (AMA), Student Marketeer for Red Bull at Pace University

Why did you choose Pace University and the Lubin School of Business?

I chose Pace University and the Lubin School of Business for the strong internship opportunities and professional connections it offers students. The wide variety of clubs also played a big role in my decision—they’ve had a life-changing impact on me.

How have clubs on campus helped enrich your student?

They’ve given me the chance to gain leadership experience early in my college career. Joining an E-Board as a second-year student helped me build a strong foundation, which eventually led to a core four E-Board role. I credit that growth to the teamwork and leadership opportunities I had early on.

What drew you to take on leadership roles in clubs like AMA, and how have those experiences shaped your time at Pace?

I was drawn to AMA because of the chance to collaborate on a team, help host events, and contribute behind the scenes. Getting to serve student needs in meaningful ways has been incredibly rewarding. These experiences helped me find my community and grow professionally.

I chose Pace University and the Lubin School of Business for the strong internship opportunities and professional connections it offers students.

What inspired your interest in your major, and how have you pursued that passion at Pace?

I was originally a finance major, but during my second semester of sophomore year, I attended the AMA International Collegiate Conference (ICC). Networking and connecting with students from around the world sparked my interest in marketing. After that, I met with my advisor and mapped out a path in Advertising and Integrated Marketing to align with my professional goals.

What has been your favorite opportunity at Pace?

Being a Student Marketer for Red Bull at Pace has been one of my favorite opportunities. It’s been an incredible experience that’s allowed me to plan events and collaborate with clubs across campus.

Do you have any advice for other Lubin students?

Get involved in clubs! Staying consistent and taking on leadership roles has transformed my professional growth. I wouldn’t have had half the experiences—or learned as much—without the amazing opportunities Pace’s clubs provide.

What does #LubinLife mean to you?

To me, #LubinLife means access to amazing professors, engaging classes, and professional development opportunities through Lubin’s many student clubs.

Connect with Anna

Press Release: Pace University Awarded Over $3 Million New York State Department of Health Grant to Strengthen Healthcare Workforce Pipeline in Region

Pace University has been awarded more than $3 million from the New York State Department of Health’s Healthcare Education and Life-skills Program (HELP) to establish the College of Health Professions Pathways to Practice Initiative (CPPI).

New initiative will expand access, strengthen pre-health advising, and prepare advanced healthcare students to address workforce shortages in the Lower and Mid-Hudson Valley

Pace University has been awarded more than $3 million from the New York State Department of Health’s Healthcare Education and Life-skills Program (HELP) to establish the College of Health Professions Pathways to Practice Initiative (CPPI).

The five-year award, providing $614,395 annually from January 2026 through December 2030, will support a comprehensive effort to strengthen the healthcare workforce pipeline across the Lower and Mid-Hudson Valley.

Led by Elizabeth Colón-Fitzgerald, EdD, associate dean of Student Success & Retention Strategies, the initiative was developed through a collaborative effort with faculty leaders Beau Anderson, Denise Tahara, Esma Paljevic, and Shannon Gribben. The project also benefited from the expertise of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) collaborators Dr. Margaret Barton-Burke and Dr. Annmarie Mazzella-Ebstein. Together, the team designed CPPI to expand access for underrepresented students, bolster advising for pre-health majors, and prepare advanced nursing and health sciences students to transition successfully into high-demand clinical roles.

“This grant is an extraordinary opportunity for Pace’s College of Health Professions to strengthen the healthcare workforce in Westchester,” said Brian Goldstein, dean of the College of Health Professions at Pace University. “Through the Pathways to Practice Initiative, we will expand access to healthcare education, support students as they prepare for advanced roles, and ensure that our graduates are ready to meet the evolving needs of patients and communities across the Lower and Mid-Hudson Valley.”

The initiative features three interconnected programs:

- CHP Scholars Program (CHP-SP): Expands access to healthcare education by supporting Black and Latino students in nursing and health sciences through financial aid, mentorship, and academic coaching.

- Pre-Health Advising Program (PHAP): Strengthens the pipeline for critical healthcare roles by providing tailored advising, career exploration, and graduate school preparation for pre-health students University-wide.

- Student-to-Practice Program (SPP): Equips final-semester NP, PA, and RN students with the tools to manage stress, enhance wellness, and build resilience through workshops and simulations facilitated by MSK and Pace faculty.

“This award not only affirms Pace University’s leadership in healthcare education, but it also represents a collaborative effort to build a stronger, more resilient healthcare workforce,” said Elizabeth Colón-Fitzgerald, EdD, associate dean of Student Success & Retention Strategies and principal investigator for the grant. “Through the Pathways to Practice Initiative, we are expanding access, strengthening support for students, and preparing graduates to thrive in the most demanding clinical environments.”

“Building on the Academic-Clinical Partnership between Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the Lienhard School of Nursing at Pace University gives us traction to prepare nurses of the future with grants like HELP,” said Margaret Barton-Burke, Ph.D., RN, FAAN, and Lisa Mazzella Ebstein, Ph.D., RN, of Nursing Research at MSK. “We will contribute by implementing resilience and emotional intelligence training. Offering this training before workforce entry can foster emotional wellness, enhance coping strategies, and mitigate burnout. Thus, supporting the well-being and efficacy of nurses. We are excited to collaborate on this important initiative over the next five years.”

This award also expands Pace University’s partnership with MSK, a global leader in clinical care, research, and training. Together, Pace and MSK are creating a model for preparing the next generation of healthcare professionals to meet the evolving needs of patients and communities across the Lower and Mid-Hudson Valley.

About Pace University

Since 1906, Pace University has been transforming the lives of its diverse students—academically, professionally, and socioeconomically. With campuses in New York City and Westchester County, New York, Pace offers bachelor, master, and doctoral degree programs to 13,600 students in its College of Health Professions, Dyson College of Arts and Sciences, Elisabeth Haub School of Law, Lubin School of Business, School of Education, and Seidenberg School of Computer Science and Information Systems.

About the College of Health Professions at Pace University

Established in 2010, the College of Health Professions (CHP) at Pace University offers a broad range of programs at the bachelor, master's, and doctoral levels. It is the College's goal to create innovative and complex programs that reflect the changing landscape of the health care system. These programs are designed to prepare graduates for impactful careers in health care practice, health-related research, or as educators, and equip graduates to work in health policy and global health fields. Students in clinical programs receive hands-on training in the College's interprofessional Center of Excellence in Healthcare Simulation and have the opportunity to apply their developing skills in real-world settings at many of the regions' leading clinical facilities. In addition to Nutrition and Dietetics, the College currently comprises several growing and important areas of study, which include nursing, physician assistant, communication sciences and disorders, health science, nutrition and dietetics, occupational therapy, health informatics, and public health.

Building Better Leaders Through the Science of Happiness

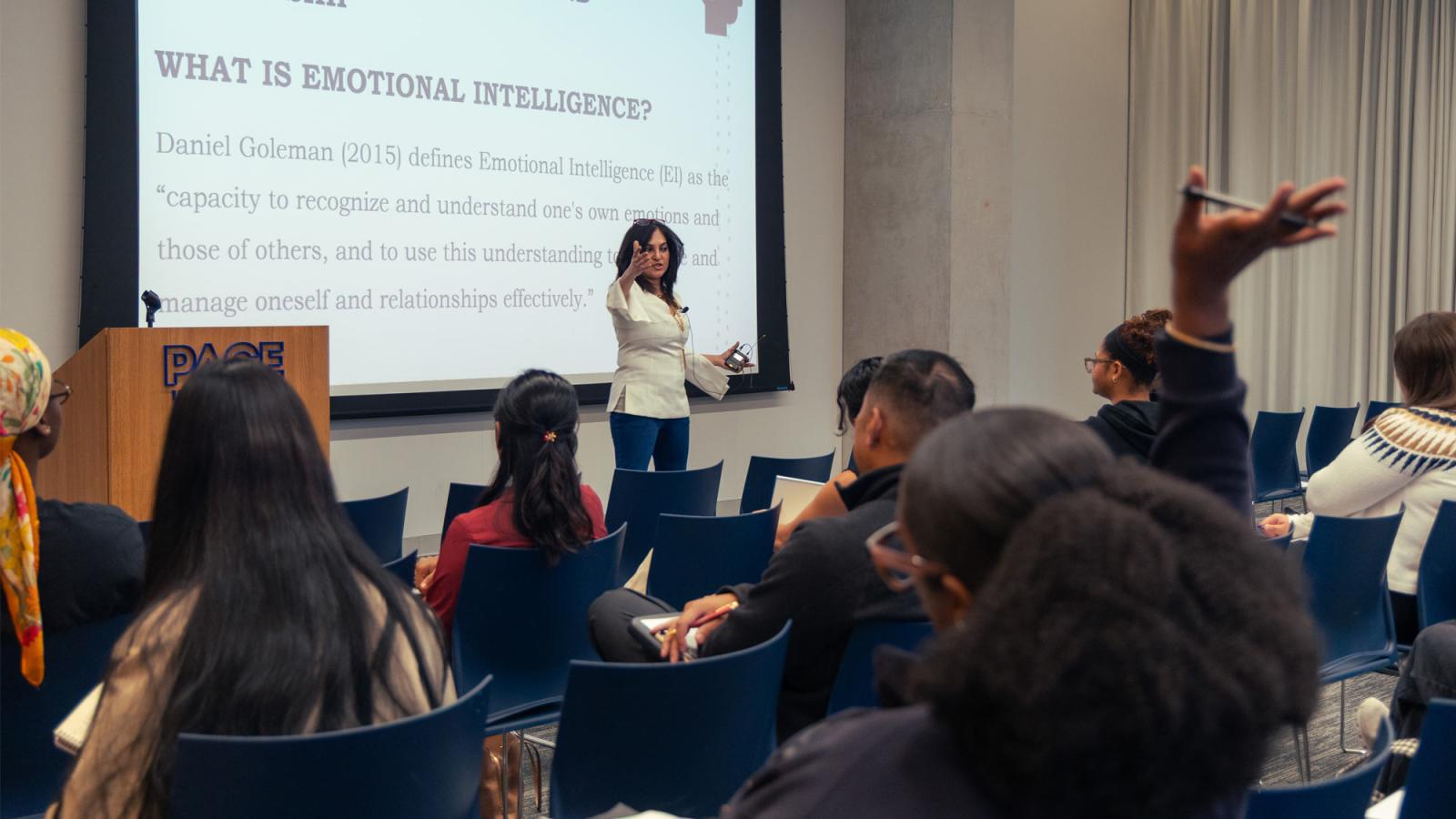

Driven by her own story of resilience, Ipshita Ray, PhD, is leading Lubin’s new Center for Leadership and Emotional Intelligence in collaboration with Harvard’s Leadership and Happiness Laboratory. Learn how this new program is helping equip the next generation of leaders through the science of happiness.

The Lubin School of Business is launching a bold new initiative this fall aimed at reshaping how students understand success—and themselves.

The Center for Leadership and Emotional Intelligence, housed within the Lubin School of Business was created in partnership with Harvard professor and Kennedy school professor Arthur Brooks, who also runs the Leadership and Happiness Laboratory. The Center introduces a free six-session, non-credit program designed to teach Pace University students the science behind happiness and how it intersects with transformative leadership.

Ipshita Ray, PhD, a graduate program chair in Lubin, is the driving force behind the center. Her vision, born from a personal journey of resilience and renewal, has transformed into a mission to empower students with tools that go beyond theory.

From Adversity to Action

Ray’s vision for the center emerged during one of the most difficult chapters of her life: a battle with stage three cancer.

“I’ve been blessed with a second chance, and my mission is not to waste it, but to do something meaningful,” she explains. “I truly believe that my Pace Community, my colleagues and friends, saved my life.”

Her return to teaching, especially during COVID-19, was met with a profound awareness of how deeply her students were struggling to navigate the world and find purpose. “I realized the students were hurting inside,” Ray says. “I didn’t want to just teach them material for academic purposes. I wanted to do something with impact.”

That “something” became a letter to Arthur Brooks, PhD, at Harvard Kennedy School. She read his book From Strength to Strength during her battle with cancer and was moved by his work at Harvard Kennedy School’s Leadership and Happiness Laboratory.

Ray reached out to Brooks and shared her story—and a proposal. She wanted to bring his work and her story to Pace.

Purposeful Partnerships

Brooks, renowned for his bestselling book Build the Life You Want (co-written with Oprah Winfrey), has long advocated for embedding the science of happiness into leadership education. His lab at Harvard creates research and training for leaders across government, business, and academia.

Ray worked in conjunction with Brooks to develop a curriculum based on his work and her own experiences here at Pace. “The lessons are designed around how happiness can be a daily practice—how you can take it from a feeling to a state of being,” Ray explains. “It’s about converting negative energy into positive energy.”

It’s about building leaders with a foundational happiness that allows them to elevate the people that surround them.

Each of the six in-person sessions focuses on a different facet of emotional intelligence and practical leadership. “This program is about building leaders who lift others up,” Ray explains. “Leaders whose main purpose is service, not wealth or power. It’s about building leaders with a foundational happiness that allows them to elevate the people that surround them.”

The center is backed by Lubin Dean Emeritus and former NBCUniversal president Neil Braun, who has pledged funding support and will co-teach the course alongside Ray, tying Ray’s curriculum into real-world leadership skills. Upon completion, students will receive a certificate indicating they’ve taken part in a curriculum designed by Harvard Kennedy School faculty in collaboration with Lubin and take part in a networking event featuring C-suite leaders and recent Pace alumni.

High Hopes for Spreading Happiness

Though the initiative launches within Lubin this fall, Ray already has high hopes for the future of the center. She hopes to expand the offering across Pace, to help bring the curriculum to other New York schools, and even establish a formal dual-degree program with Harvard.

“I want to make this a major movement,” she says. “My hope is to expand the program University-wide, which would allow Harvard to list us on their website, invite us to symposia, and co-lead research.”

I want to make this a major movement.

Her goal for the present, however, is to help the students of Pace right now.

“How can you lead if you don’t see the value in yourself or others?” Ray asks. Her hope in bringing the science of happiness to Pace students is to empower them to not only learn and lead better, but to live better.

In an era where young people feel more alone and purposeless than ever, Ray believes programs like this are not just helpful, they’re necessary. “I want students to understand they have complete agency over their choices,” Ray says. “I believe a winning life is a choice, that happiness is a choice.”

The Center for Leadership and Emotional Intelligence is open to all Lubin students. Learn more about the Center and how you can get involved.

More from Pace

At 25, Soumyadip Chatterjee ’23 began his Pace journey. By 27, he was the youngest senior software engineer on a major project at Wells Fargo. Read his story to see how he turned challenges into motivation to go further.

Your Commencement isn’t just about walking the stage—it’s about celebrating the people and values that got you here. That’s why we want the Class of 2026 to help choose our Commencement speaker and the recipient of the Opportunitas in Action Award. Think of someone whose story will light up the room, inspire your classmates, and leave a lasting mark. Ready? Nominate now.

The Pace Energy and Climate Center (“PECC") is thrilled to announce the 2025–2026 Executive Board, which is comprised of three exceptional Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University students committed to advancing PECC’s mission and outreach.